---

title: Python Programming

date: 2020-09-09

published-title: Created

date-modified: last-modified

title-block-banner: "#212529"

toc-title: "Contents"

---

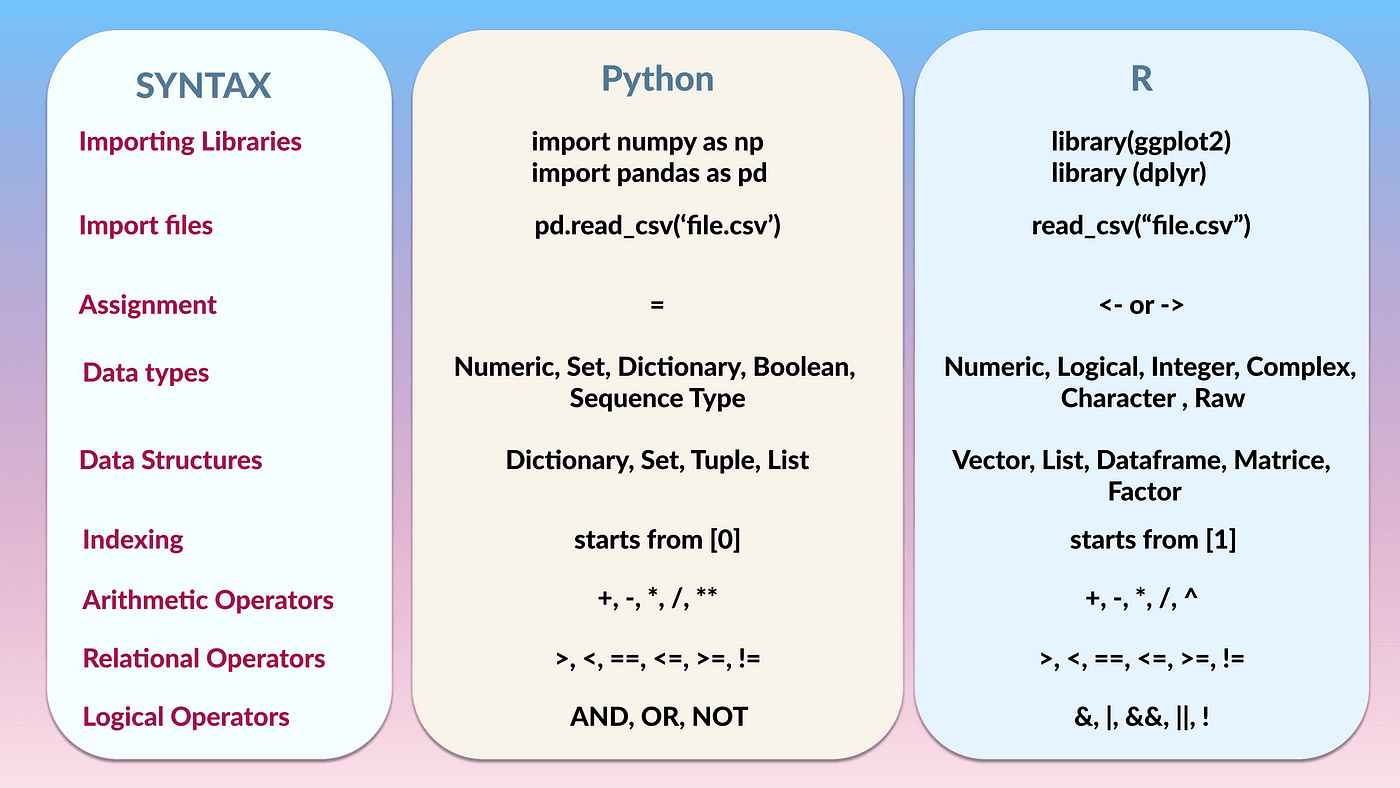

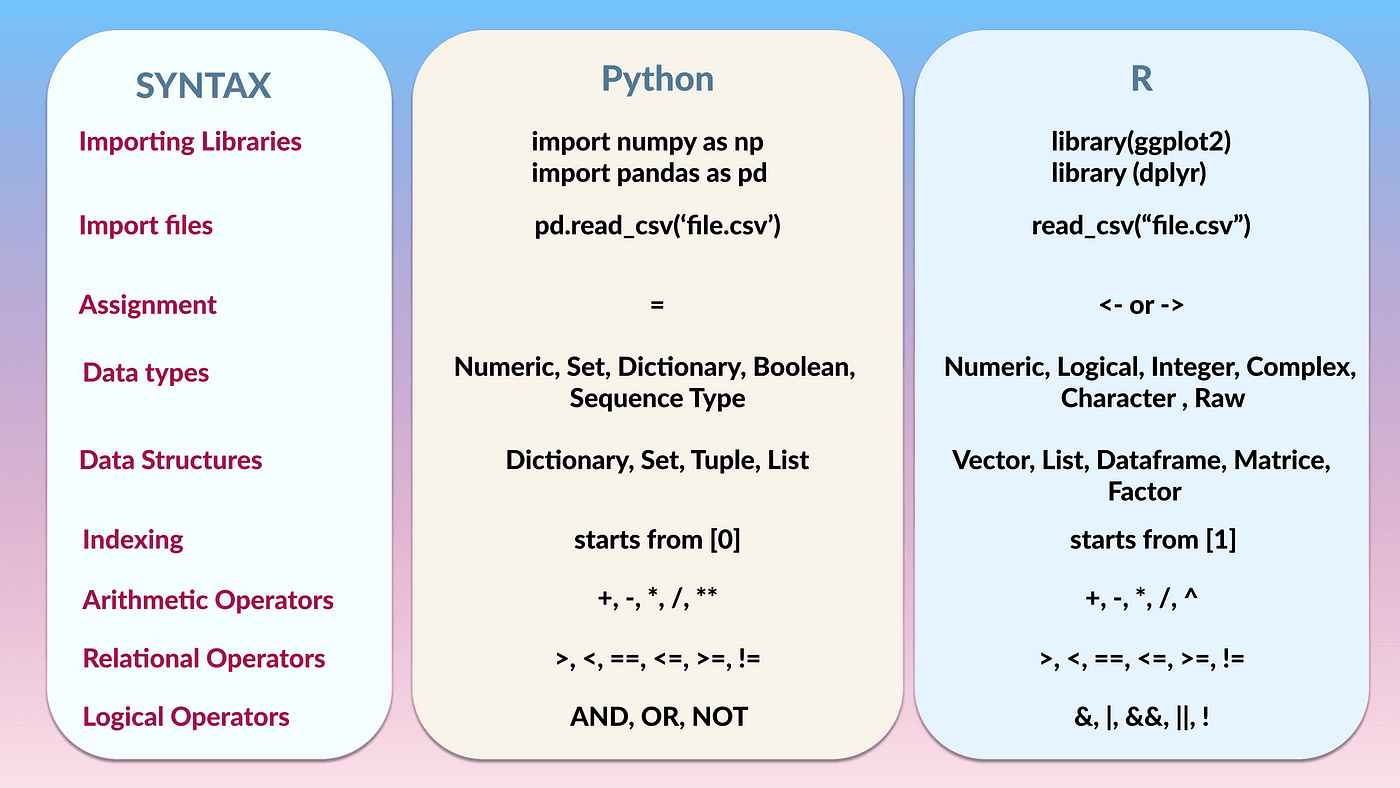

{width=800px}

## Data Stuctures

{width=800px}

in Python, understanding data types and structures is essential for writting

effective code. Data types determine the kind of data a variable can hold,

while data structures allow you to organize and manage that data efficiently.

- Numbers: Represent numerical values, including integers and floating-point numbers.

- Strings: Represent sequences of characters, used for text manipulation.

- Booleans: Represent truth values, either True or False.

- Lists: Ordered collections of items, allowing for duplicate values and mutable operations.

- Dictionaries: Unordered, Key-value pairs that allow for efficient data retrieval based on unique keys.

- Tuples: Ordered collections of items, similar to lists but immutable.

- Sets: Unordered collections of unique items, useful for membership testing and eliminating duplicates.

```{python}

## Numbers and strings

integer_num = 42

float_num = 3.14

string_text = "Hello, Python!"

## List: mutable, ordered collection

fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"]

## Tuple: immutable, ordered collection

dimensions = (1920, 1080)

## Dictionary: unordered, key-value pairs

person = {"name": "Alice", "age": 30, "city": "New York"}

## Set: unordered collection of unique items

unique_numbers = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

print("Integer:", integer_num)

print("Float:", float_num)

print("String:", string_text)

print("List of fruits:", fruits)

print("Tuple of dimensions:", dimensions)

print("Dictionary of person:", person)

print("Set of unique numbers:", unique_numbers)

```

## Variable

- `Number`

- `String`

- `Tuple`

- `List`: Mutable, container

- `Dictionary`: Mutable, container

- `Set`: Mutable, container

- `None`: empty value

```{python}

tuple = (1, 2, 3)

list = [1, 2, 3]

dict = {"ele1":1, "ele2":2, "ele3":3}

```

## Operator

Numerical Operators:

- `< ` : less than

- `> ` : greater than

- `<=` : less than or equal to

- `>=` : greater than or equal to

- `==` : equal to

- `!=` : not equal to

String Operators:

- `==` : equal to

- `!=` : not equal to

Logical Operators:

- and

- or

- not

## Control flow

Control flow in Python allows you to make decisions and execute different blocks of code based on conditions.

Loops enable you to repeat a block of code multiple times.

Best practices for control flow and loops include:

- Keep conditions simple and clear. Break down complex conditions into smaller parts.

- Use meaningful variable names to enhance readability.

- Avoid deeply nested loops and conditions to maintain code clarity.

- Use comments to explain the purpose of complex conditions or loops.

- Test edge cases to ensure your control flow behaves as expected.

```{python}

#| eval: false

# Conditional statements

x = 10

if x > 5:

print("x is greater than 5")

elif x == 5:

print("x is equal to 5")

else:

print("x is less than 5")

```

## Iteration

```{python}

#| eval: false

## For loop: iterating over a list

for i in range(5):

print("Iteration:", i)

## While loop: continues until a condition is met

count = 0

while count < 5:

print("Count is:", count)

count += 1

```

Conditional execution in Python is achieved using the if/else construct (if and else are reserved words).

```{python}

#| eval: false

# Conidtional execution

x = 10

if x > 10:

print("I am a big number")

else:

print("I am a small number")

# Multi-way if/else

x = 10

if x > 10:

print("I am a big number")

elif x > 5:

print("I am kind of small")

else:

print("I am really number")

```

## Loops

Two looping constructs in Python

- `For` : used when the number of possible iterations (repetitions) are known in advance

- `While`: used when the number of possible iterations (repetitions) can not be defined in advance. Can lead to infinite loops, if conditions are not handled properly

```{python}

#| eval: false

for customer in ["John", "Mary", "Jane"]:

print("Hello ", customer)

print("Please pay")

collectCash()

giveGoods()

hour_of_day = 9

while hour_of_day < 17:

moveToWarehouse()

locateGoods()

moveGoodsToShip()

hour_of_day = getCurrentTime()

```

What happens if you need to stop early? We use the `break` keyword to do this.

It stops the iteration immediately and moves on to the statement that follows the looping

```{python}

#| eval: false

while hour_of_day < 17:

if shipIsFull() == True:

break

moveToWarehouse()

locateGoods()

moveGoodsToShip()

hour_of_day = getCurrentTime()

collectPay()

```

What happens when you want to just skip the rest of the steps? We can use the `continue` keyword for this.

It skips the rest of the steps but moves on to the next iteration.

```{python}

#| eval: false

for customer in ["John", "Mary", "Jane"]:

print("Hello ", customer)

print("Please pay")

paid = collectCash()

if paid == False:

continue

giveGoods()

```

## Exceptions

- Exceptions are errors that are found during execution of the Python program.

- They typically cause the program to fail.

- However we can handle them using the ‘try/except’ construct.

```{python}

#| eval: false

num = input("Please enter a number: ")

try:

num = int(num)

print("number squared is " + str(num**2))

except:

print("You did not enter a valid number")

```

```{python}

#| eval: false

help()

type()

len()

range()

list()

tuple()

dict()

```

## Library

* Install library

::: {.panel-tabset group="language"}

#### Python

```{.bash}

#| eval: false

## Install library using pip

python3 -m pip install pandas numpy matplotlib

```

#### R

```{.r}

## Install package using install.packages()

install.packages("dplyr")

## Install package using devtools

install.packages("devtools")

devtools::install_github("tidyverse/dplyr")

## Install package using bioconductor

if (!requireNamespace("BiocManager", quietly = TRUE))

install.packages("BiocManager")

BiocManager::install("dplyr", force = TRUE, ask = FALSE)

```

#### Conda

```{.bash}

#| eval: false

## Install Python library using conda

conda install pandas numpy matplotlib

## Install R package using conda

conda install -n renv r-dplyr bioconductor-dplyr

```

:::

* Load library

::: {.panel-tabset group="language"}

#### Python

```{.python}

#| eval: false

## Load library

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

## Use a function from library, first specify the library nickname and then

## the function name, separated by a dot:

np.log(7)

```

#### R

```{.r}

#| eval: false

## Load library

library(dplyr)

suppressPackageStartupMessages(

suppressWarnings(

{

library(ggplot2)

library(tidyr)

}

)

)

```

:::

## Whitespace

- Whitespace matters in Python.

- in R, code blocks are defined by curly braces `{}`.

- in Python, code blocks are defined by indentation (usually 4 spaces).

::: {.panel-tabset group="language"}

#### R

```{.r}

if(TRUE) {

print("This is R")

if(TRUE) {

print("Nested block in R")

}

}

```

#### Python

```{.python}

## Python accepts tabs or spaces, but spaces are preferred

if True:

print("This is Python")

if True:

print("Nested block in Python")

```

:::

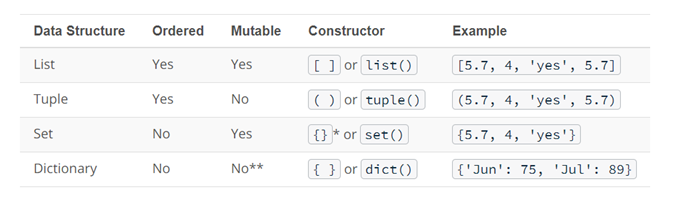

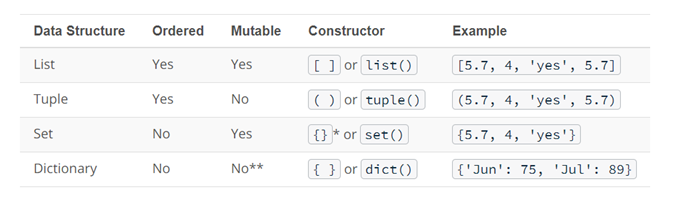

## Containers

* in R, the `list` is a versatile container type that can hold elements of different types and structures.

* There is no single direct equivalent of R's `list` in Python that support all the same features.

* Instead, there are (at least) 4 different Python container types we need to aware:

+ `list`: ordered, mutable, allows duplicate elements, created using `[]`

+ `tuple`: ordered, immutable, allows duplicate elements, created using `()`

+ `set`: unordered, mutable, no duplicate elements, created using `{}`

+ `dict`: unordered, mutable, key-value pairs, created using `{}`

#### Lists

Python lists created using bare brackets `[]`, closer to R's `as.list` function.

* The most important thing to know about Python lists is that they are mutable.

```{python}

#| eval: false

x = [1, 2, 3]

y = x # `y` and `x` now refer to the same list!

x.append(4)

print("x is", x)

#> x is [1, 2, 3, 4]

print("y is", y)

#> y is [1, 2, 3, 4]

```

* Some syntactic sugar around Python lists you might encounter is the usage of + and * with lists.

These are concatenation and replication operators, akin to R’s c() and rep().

```{python}

#| eval: false

x = [1]

x

#> [1]

x + x

#> [1, 1]

x * 3

#> [1, 1, 1]

```

* Index into lists with integers using trailing `[]`, but note that indexing is 0-based

```{python}

#| eval: false

x = [1, 2, 3]

x[0]

#> 1

x[1]

#> 2

x[2]

#> 3

try:

x[3]

except Exception as e:

print(e)

#> list index out of range

## Negative numbers count from the end of the list

x[-1]

#> 3

x[-2]

#> 2

x[-3]

#> 1

```

* Slice ranges of lists using `:` inside the trailing `[]`. Note that the end index is exclusive. We can optionally specify a stride using a second `:`.

```{python}

#| eval: false

x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

x[0:2] # get items at index positions 0, 1

#> [1, 2]

x[1:] # get items from index position 1 to the end

#> [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

x[:-2] # get items from beginning up to the 2nd to last.

#> [1, 2, 3, 4]

x[:] # get all the items (idiom used to copy the list so as not to modify in place)

#> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

x[::2] # get all the items, with a stride of 2

#> [1, 3, 5]

x[1::2] # get all the items from index 1 to the end, with a stride of 2

#> [2, 4, 6]

```

#### Tuples

* Tuples behave like lists, but are immutable (cannot be changed after creation).

* Created using bare parentheses `()`, but parentheses are not strictly required.

```{python}

#| eval: false

#| output: asis

x = (1, 2) # tuple of length 2

type(x)

#> <class 'tuple'>

len(x)

#> 2

x

#> (1, 2)

x = (1,) # tuple of length 1

type(x)

#> <class 'tuple'>

len(x)

#> 1

x

#> (1,)

x = () # tuple of length 0

print(f"{type(x) = }; {len(x) = }; {x = }")

#> type(x) = <class 'tuple'>; len(x) = 0; x = ()

# example of an interpolated string literals

x = 1, 2 # also a tuple

type(x)

#> <class 'tuple'>

len(x)

#> 2

x = 1, # beware a single trailing comma! This is a tuple!

type(x)

#> <class 'tuple'>

len(x)

#> 1

```

* Tuples are the container that powers the packing and unpacking semantics in Python.

+ Packing and unpacking tuples is a common idiom in Python.

+ Python provides the convenience of unpacking tuples into multiple variables in a single statement.

```{python}

#| eval: false

x = (1, 2, 3)

a, b, c = x

a

#> 1

b

#> 2

c

#> 3

```

Tuple unpacking can occur in a variety of contexts, such as iteration:

```{python}

#| eval: false

xx = (("a", 1), ("b", 2))

for x1, x2 in xx:

print("x1 = ", x1)

print("x2 = ", x2)

#> x1 = a

#> x2 = 1

#> x1 = b

#> x2 = 2

```

Python raises an error when attampt to unpack a container to the wrong number of symbols:

```{python}

#| eval: false

x = (1, 2, 3)

a, b, c, =x # success

a, b = x # error, x has too many values to unpack

#> ValueError: too many values to unpack (expected 2)

a, b, c, d = x # error, x has not enough values to unpack

#> ValueError: not enough values to unpack (expected 4, got 3)

```

Unpack a variable number of values using the `*` operator:

```{python}

#| eval: false

x = (1, 2, 3)

a, *the_rest = x

a

#> 1

the_rest

#> [2, 3]

```

Unpack the nested structures:

```{python}

#| eval: false

x = ((1, 2), (3, 4))

(a, b), (c, d) = x

```

#### Dictionaries

* Dictionaries can be created using syntax like {key: value, key: value, ...}.

* Note that `r_to_py` converts R named lists to Python dictionaries.

```{python}

#| eval: false

d = {

"key1": 1,

"key2": 2

}

d2 = d

d

#> {'key1': 1, 'key2': 2}

d["key1"]

#> 1

d["key3"] = 3

d2 # modified in place!

#> {'key1': 1, 'key2': 2, 'key3': 3}

```

* Cannot index into dictionaries using integer indices. Instead, use the keys.

```{python}

#| eval: false

d = {"key1": 1, "key2": 2}

d[1] # error

#> KeyError: 1

```

#### Sets

Sets are a container that can be used to efficiently track unique items or deduplicate lists. They are constructed using `{val1, val2}` (like a dictionary, but without `:`). Think of them as dictionary where you only use the keys. Sets have many efficient methods for membership operations, like `intersection()`, `issubset()`, `union()` and so on.

```{python}

#| eval: false

s = {1, 2, 3}

type(s)

#> <class 'set'>

s

#> {1, 2, 3}

s.add(1)

s

#> {1, 2, 3}

```

## Dataframe

::: {.panel-tabset group="language"}

#### R

```{.r}

#| eval: true

## R contains a native data frame

r_df <- data.frame(

Name = c("Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"),

Age = c(25, 30, 35),

City = c("New York", "Los Angeles", "Chicago")

)

print(r_df)

```

#### Python

```{.python}

#| eval: true

## Python's dataframe comes form the pandas library

import pandas as pd

## It's actually a type of dictionary of lists

py_df = pd.DataFrame(

{

'Name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie'],

'Age': [25, 30, 35],

'City': ['New York', 'Los Angeles', 'Chicago']

}

)

print(py_df)

```

:::